This guide will examine mortgage-backed securities, what they are and how they work, as well as the risks involved with this particular investment product. Furthermore, we will also delve into the pitfalls of the MBS market leading up to the eventual 2008 housing crash and how it ultimately changed the housing market.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

30+ million UserseToro is a multi-asset investment platform. The value of your investments may go up or down. Your capital is at risk. Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

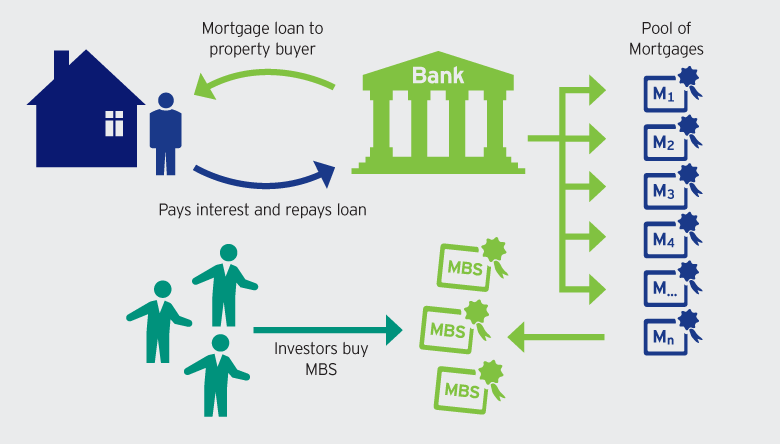

A mortgage-backed security (MBS) is a specific type of asset-backed security (similar to a bond) backed by a collection of home loans bought from the banks that issued them. The investor who buys mortgage-backed securities is essentially lending money to home buyers. Essentially, the MBS turns the bank into a mediator between the homebuyer and MBS investors.

As a result, a bank can grant mortgages to its clients and then sell them at a discount to be bundled as MBSs to investors as a type of collateralized bond. The bank reports the sale as a plus on its balance sheet and risks nothing if the homebuyer defaults on their loan.

In return, the investor gets the rights to the value of the mortgage, including interest and principal payments made by the borrower. However, if the homeowner defaults, the investor who paid for the mortgage-backed security won’t get paid, which means they could lose money. Therefore, an MBS is only as sound as the mortgages that back it up, a fact that became painfully evident during the subprime mortgage meltdown of 2007-2008.

Typical buyers of MBS include individual investors, corporations, and institutional investors. Two primary types of MBSs are pass-throughs and collateralized mortgage obligations (CMO). An MBS is traded on the secondary market and can be bought and sold through a broker. The minimum investment varies between issuers.

Today, an MBS can only be issued by a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) or a private financial company to be sold on the markets. In addition, the mortgages have to originate from a regulated and authorized financial institution. Moreover, the MBS must have received one of the top two ratings issued by an accredited credit rating agency.

Asset-backed securities (ABS) are a type of financial investment backed by an underlying pool of assets, typically ones that generate a cash flow from debt (e.g., loans, credit card receivables). They generally take the form of a bond or note, paying income at a fixed rate for a predefined amount of time until maturity. Mortgage-backed securities, too, can be considered types of ABS.

Beginners’ corner:

Following The Great Depression of the 1930s, when the government established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to assist in rehabilitating and constructing residential houses. In addition, the agency aided in developing and standardizing the fixed-rate mortgage and popularizing its usage.

Then, in 1938, the government created Fannie Mae, a government-sponsored enterprise, to create a liquid secondary market for these mortgages and thereby free up capital from banks to generate more loans, mainly by buying FHA-insured mortgages.

Fannie Mae was later split into Fannie Mae and Ginnie Mae to support the FHA-insured mortgages, Veterans Administration, and Farmers Home Administration-insured mortgages. Finally, in 1970, the government created another agency, Freddie Mac, to perform similar functions to Fannie Mae’s.

MBSs allowed non-bank financial institutions to enter the mortgage business. Before MBSs, only banks had significant enough deposits to make long-term loans or the capacity to wait until these loans were repaid decades later.

The invention of MBSs meant lenders immediately got their cash back from investors on the secondary market, freeing up funds to lend to more homeowners. As a result, the number of lenders skyrocketed. For example, some offered mortgages that didn’t look at a borrower’s job or assets, creating more competition for traditional banks, which, in turn, had to lower their standards to compete.

Unfortunately, MBSs were not regulated. The federal government regulated banks to protect their depositors, but those rules didn’t apply to MBSs and mortgage brokers. So though bank depositors were safe, MBS investors were not covered.

First, a bank or a financial institution provides a home loan to one of its customers. It then sells that loan to an investment bank. Finally, it uses the money received from the investment bank to make new loans.

Next, the investment bank takes the original loan and adds it to a bundle of mortgages based on the credit quality attached to the underlying security and markets them to investors.

The investors then buy the MBSs (similar to a bond) and collect monthly income (principal and interest) while holding them. So, in principle, if the customer pays off their mortgage, the MBS investor profits.

Coupons (interest rate) are allocated based on the loan credit ratings, with lower-rated securities having higher coupon rates to lure in investors.

The majority of mortgage-backed securities are offered by an entity of the U.S. government, such as:

As a result, they are often classified together in what is known as government-supported mortgage-backed securities.

The Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA), commonly referred to as Ginnie Mae, is a federal government corporation that secures the principal and interest payments on mortgage-backed securities issued by approved lenders. Ginnie Mae’s goal is to ensure affordable home loans for underserved consumers in the mortgage market.

The Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), commonly known as Fannie Mae, is a publically owned government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) established in 1938 by Congress during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal.

It was formed to stimulate the housing market by making more mortgages available to moderate-to low-income borrowers. Rather than providing loans, it backs or guarantees them in the secondary mortgage market.

The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. (FHLMC), familiar as Freddie Mac, is a publically owned, government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) chartered in 1970 by Congress to keep money flowing to mortgage lenders to support homeownership and rental housing for middle-income citizens. The role of Freddie Mac is to purchase loans from mortgage lenders, then merge them and sell them as MBSs.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are both publicly traded GSEs, with their primary difference being that Fannie Mae buys mortgage loans from major retail or commercial banks, while Freddie Mac gets its loans from smaller banks.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were bailed out by the U.S. government following the financial crisis and delisted from the NYSE. Today, Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s shares are traded over-the-counter (OTC), meaning you can’t buy them on a major stock exchange.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

30+ million UserseToro is a multi-asset investment platform. The value of your investments may go up or down. Your capital is at risk. Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

There are three basic types of mortgage-backed security:

The simplest MBS is the pass-through mortgage-backed security. Pass-throughs are constructed as trusts in which mortgage payments are received and passed through as principal and interest payments to bondholders. They typically come with stated maturities of five, 15, or 30 years.

However, the average life of a pass-through may be less than the stated maturity depending on the principal payments on the mortgages that assemble the pass-through.

A collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) is a financial product backed by a pool of mortgages bundled together and sold as an investment. CMOs generate cash flow as borrowers repay the mortgages that act as collateral on these securities. This, in turn, is distributed to investors as principal and interest payments based on predefined agreements.

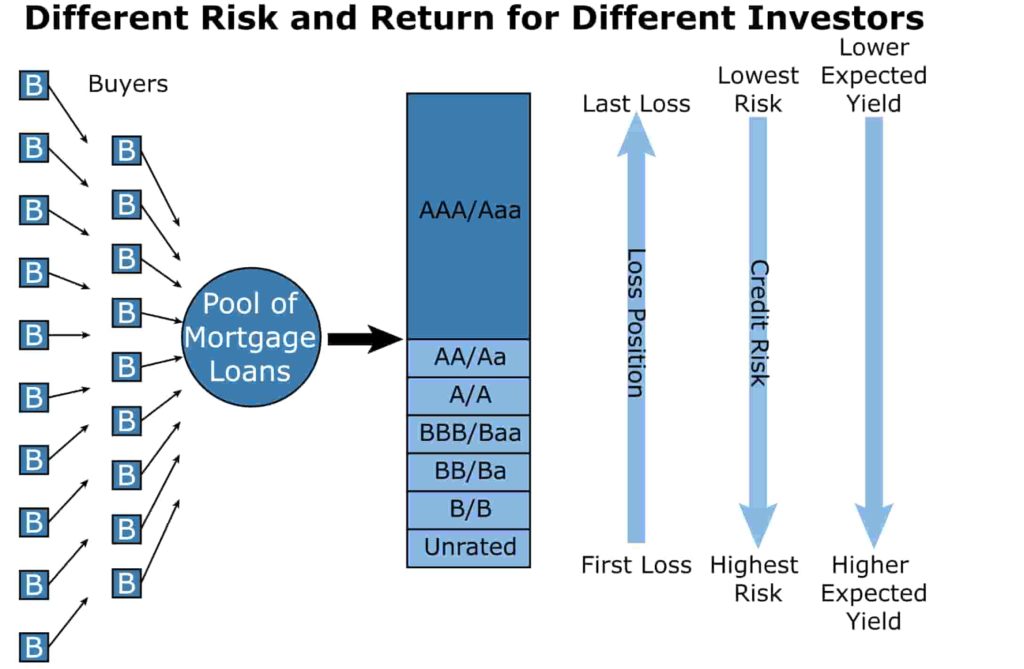

Collateralized mortgage obligations are organized by slicing a pool of mortgages into similar risk profiles known as tranches. Tranches are given different credit ratings and generally have different principal balances, interest rates, maturity dates, and the potential for repayment defaults.

The less risky tranches have more certain cash flows and a lower degree of exposure to default risk, while riskier tranches have more uncertain cash flows and more significant exposure to default risk. The elevated level of risk, however, is compensated with higher interest rates.

Collateralized mortgage obligations are influenced by interest rate changes as well as economic conditions, like foreclosure rates, refinance rates, as well as the rates and amounts at which properties are sold. Therefore, each tranche has a different size and maturity date, and bonds with monthly coupons (with principal and interest rate payments) are issued against it.

Imagine an investor with a CMO comprised of thousands of mortgages. Their profit potential depends on whether the mortgage holders repay their mortgages. If only a couple of homeowners default on their mortgages and the rest make payments as expected, the investor recoups their principal and interest.

Conversely, if thousands of people cannot make their mortgage payments and go into foreclosure, the CMO loses money and cannot pay the investor.

Like CMO, collateralized debt obligation (CDO) is a complex structured finance product backed by a pool of loans (in this case, various types, e.g., mortgages, credit card debt, student loans) and other assets sold to institutional investors by investment banks.

CDOs, too, generate cash flow as lenders repay the loans that act as collateral on these securities. The principal and interest payments are then redirected to the investors in the pool. If the underlying loans fail, the banks transfer most of the risk to the investor, typically a large hedge fund or a pension fund.

Banks slice CDOs into various risk levels or tranches. The least risky tranches have more certain cash flows and a lower degree of exposure to default risk. At the same time, riskier tranches have more uncertain cash flows and greater exposure to default risk but offer higher interest rates to attract investors.

Each tranche has a perceived (or stated) credit rating, which measures its risk of default (the failure to make required interest or principal repayments on a loan or financial instrument).

The top tier rating is usually ‘AAA‘ rated senior tranche. The middle tranches are typically called mezzanine tranches and generally carry ‘AA‘ to ‘BB‘ ratings, and the lowest or unrated tranches are referred to as the equity tranches. Each rating determines the amount of principal and interest each tranche receives.

The senior tranche is the first to soak up cash flows and the last to absorb loan defaults or missed payments. Therefore, it has the most predictable cash flow and is usually thought to carry the least risk. In contrast, the lowest-rated tranches usually only receive principal and interest payments after all other tranches are paid. On top of this, they are first in line to absorb defaults and late fees.

CDOs can also be made up of a pool of prime loans, near-prime loans (called Alt.-A loans), risky subprime loans, or a combination of the above.

Additionally, some structures use leverage and credit derivatives that can render even the senior tranche risky. These structures can become synthetic CDOs backed merely by derivatives and credit default swaps made between lenders and in the derivative markets.

Watch the video: Ryan Gosling (The Big Short) explains the structure of a basic mortgage bond:

Mortgage-backed securities come in two main varieties: commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS).

CMBS are backed by large commercial loans, referred to as CMBS or conduit loans. RMBS are backed by residential mortgages (e.g., home equity loans, Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured loans).

While the underlying loans backing RMBS are strictly residential real estate, most often single-family homes, the underlying loans that are pooled into CMBS include loans on income-producing commercial properties such as apartment buildings, factories, hotels, office buildings, shopping malls, etc.

Both CMBS and RMBS are structured into various tranches based on the risk of the loans. The senior tranches get paid off first in the case of a loan default, while lower tranches will be compensated later (or not at all) should the borrowers fail to meet payments.

Mortgage-backed securities exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that focus on securities provide an opportunity for fixed-income investors to get exposure to this market. Three examples of ETFs that invest in mortgage-backed securities are:

Low-quality MBSs were among the factors that led to The Great Recession of 2008. Even though the U.S. federal government regulated the financial institutions that assembled MBSs, there was a lack of laws governing them directly.

The absence of regulation meant that financial institutions could get their money instantly by selling MBS products immediately after making the loans. Still, investors in MBS were practically not protected at all, and if the borrowers of mortgages defaulted, there wasn’t a concrete way to compensate MBS investors.

Ultimately, investors were more likely to focus on the steady revenue offered by CMOs and other MBS securities rather than the underlying mortgages’ health. As a result, many purchased CMOs full of subprime mortgages, adjustable-rate mortgages, mortgages held by lenders whose income wasn’t verified, and other risky mortgages with a high likelihood of default.

As the market attracted various mortgage lenders, including non-bank financial institutions, traditional lenders were forced to lower their credit standards to compete in the home loan business. Simultaneously, the U.S. government pressured banks to extend mortgage financing to higher credit risk borrowers, creating massive amounts of mortgages with an increased risk of default. In short, many borrowers got into loan obligations that they could not afford.

However, with a steady supply of, and increasing demand for, mortgage-backed securities, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae aggressively supported the market by issuing ever more MBS. But unfortunately, the MBS created were increasingly low-quality, high-risk investments.

And though rising housing prices made mortgages look like fail-proof investments, market and economic conditions instituted a spike in foreclosures and payment risks that financial models did not accurately predict.

Eventually, when mortgage borrowers began to default on their loans, it led to a domino effect of collapsing the housing market and wiping out trillions of dollars from the U.S. economy. Moreover, the impact of the sub-prime mortgage crisis spread to other countries around the globe.