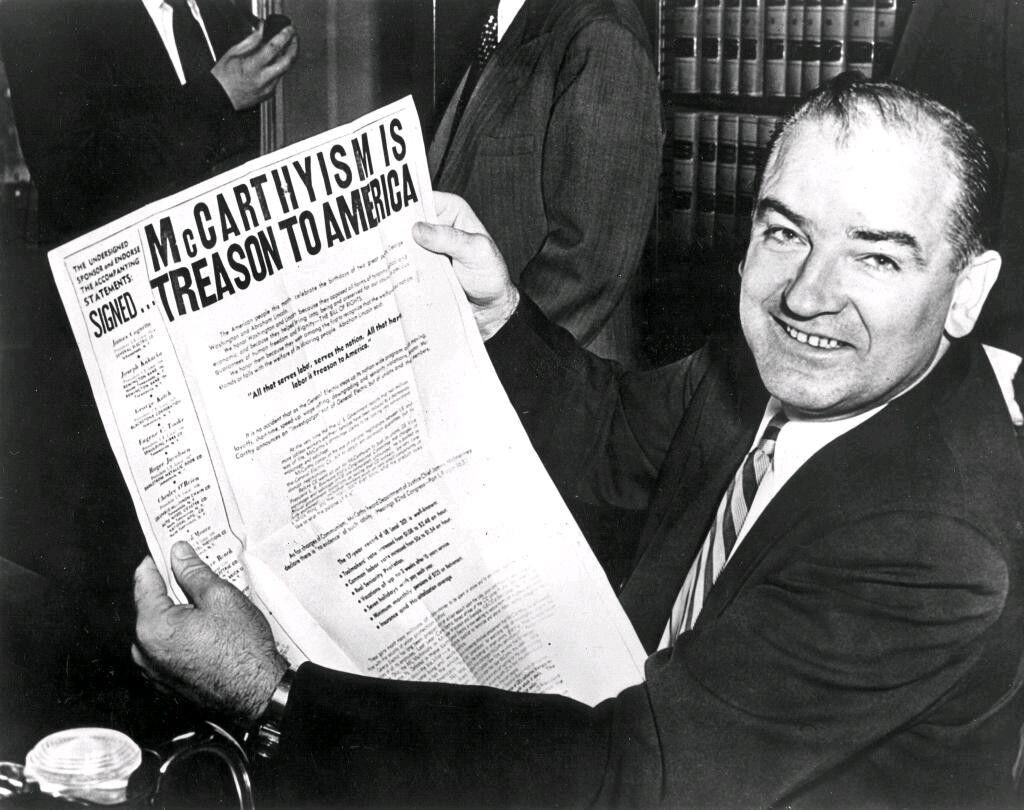

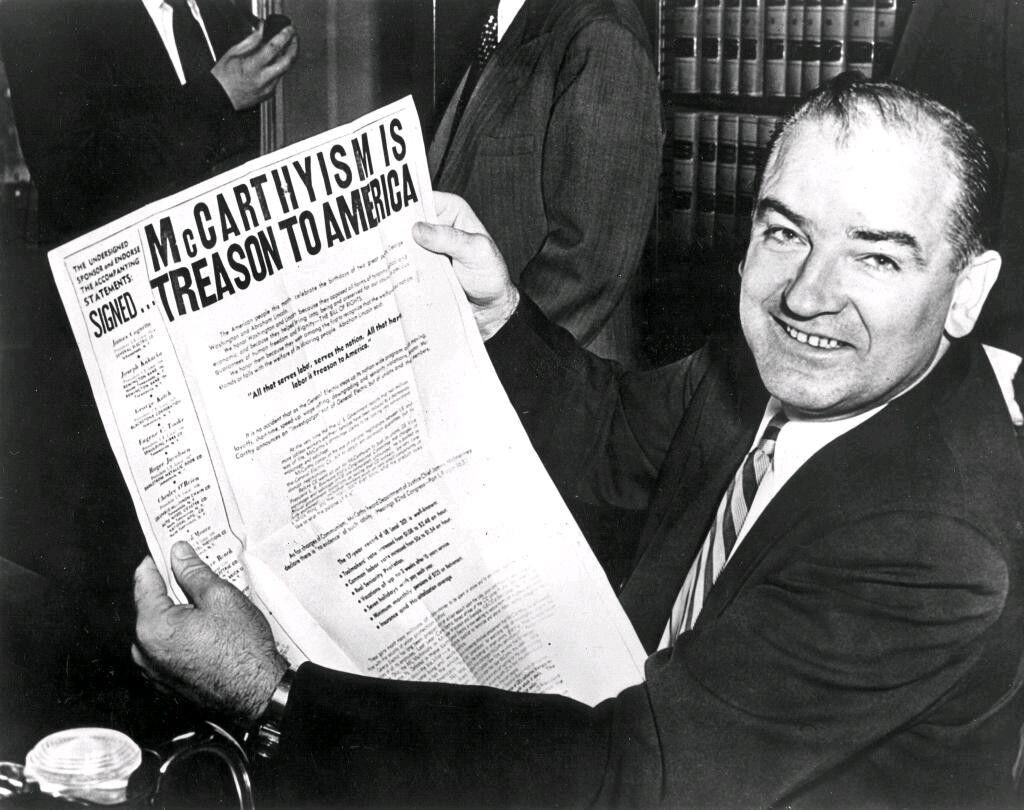

Shortly after WWII a phenomenon known as McCarthyism began to emerge in American politics. McCarthyism was the practice of investigating and accusing persons in positions of power or influence of disloyalty, subversion (working secretly to undermine or overthrow the government), or treason. Reckless accusations that the government was full of communists were pursued by Republican-led committees with subpoena power and without proper regard for evidence. The two Republicans most closely associated with McCarthyism were the phenomenon’s namesake, Senator Joseph McCarthy, and Senator Richard Nixon, who served as Vice President from 1953-1961, and then President from 1969-1974. Both men were driven by personal insecurities as much as by political gain.

Government employees, the entertainment industry, educators, and union activists were the primary targets of McCarthyism. Their communist (or leftist) associations were often greatly exaggerated, and they were often dismissed from government jobs or imprisoned with inconclusive, questionable, and sometimes outright fabricated evidence. Most verdicts were later overturned, most dismissals later declared illegal, and some laws used to convict later declared unconstitutional. The most famous examples of McCarthyism are the investigation into the leftist influence of the motion picture industry by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and investigations conducted by Senator McCarthy’s Senate sub-committee, culminating in 1954 with hearings about subversion within the Army. Both committees were provided information by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under Director J. Edgar Hoover.

In addition to these investigations, several high profile Americans were smeared by McCarthyism, including General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff during WWII and chief architect of the Marshall Plan, and Dean Acheson, President Truman’s Secretary of State and chief architect of American foreign policy during the early stages of the Cold War. McCarthyism, now discredited by all but the most rabid right-wingers, caused enormous conflict within American society.

McCarthyism began well before Senator Joseph McCarthy arrived on the scene, and its origins are complicated. Much of it was rooted in fear and anxiety within the Republican Party’s reactionary fringe. The United States had experienced a similar phenomenon from 1917-1920 in reaction to the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, which represented the emergence of communism as a political movement. Civil liberties were strictly curtailed by the Espionage and Sedition Acts, especially free speech.

After the war, a wave of leftist bombings, labor discontent, and a distrust of immigrants resulted in the First Red Scare, characterized by aggressive Justice Department investigations, severe violations of civil liberties, mass arrests and deportations, and several high-profile convictions. But during the 1930s the Communist Party of the United States gained influence as the image of Communism improved. They championed labor rights and were the bitter enemies of right-wing fascists, especially Nazis. During the worst of the Great Depression, some Americans questioned whether capitalism had failed. Some sincerely believed in the egalitarian promise of communism (and were later bitterly disappointed by its repressive tendencies). Others experimented with leftist ideas as a youthful indiscretion–because it had become popular on campus or within their social circles. During WWII, with the United States and the Soviet Union temporarily allies, anti-communist rhetoric mostly ceased. With the war’s end, however, the Soviets quickly reneged on the promise to hold free elections in territory conquered from Germany and instead installed repressive puppet regimes. Much of Central and Eastern Europe had been freed from Nazism only to become satellite nations of the Soviet Union.

The disillusionment of the post-war failure to free the peoples of Europe gave rise to the bitter winds of the Cold War. Fear and anxiety of Soviet domination was aggravated by revelations of Soviet spying on the West. Just a month after V-J Day, a cipher clerk working in the Soviet Embassy in Canada defected, bringing with him 109 documents detailing Soviet spying in Canada. Another Soviet Spy, this time an American, defected in 1945. Elizabeth Bentley had taken an interest in communism in the 1930s through her studies abroad and at Columbia University in New York. She joined the Communist Party of the United States in 1935. Bentley eventually became a spy for the Russians, first unwittingly, then willingly, through a lover. All of her spying was done during WWII, and the information passed to her by spies in the American government, which she then passed on to Moscow, had to do with what the United States knew about Germany. In 1945 she became disillusioned with her role and contacted the FBI. She subsequently named about 150 persons within the government as her contacts, many of whom were already known to investigators. The American public found out about Bentley in July 1948, and it fanned the flames of McCarthyism.

Even more troubling was the revelation that the Soviets had spied on the West’s atomic research. In 1946 the U.S. and Great Britain cracked one of the Soviet codes and learned that a scientist who had worked on the Manhattan Project and was currently working in Great Britain’s atomic research facilities was a spy. Klaus Fuchs was a German communist who had fled his homeland to escape the Nazis. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he sincerely believed that the Soviets had a right to the atomic secrets being kept from them by their allies. Fuchs was arguably the most important spy in the Cold War. He passed on secrets that enabled the Soviet Union to end the U.S. monopoly on atomic weapons only 4 years after Hiroshima, and gave them critical information about American atomic capabilities that helped Joseph Stalin conclude the U.S. was not prepared for a nuclear war at the end of the 1940s, or even in the early 1950s.

With this information the Soviets strategized that the U.S. could not deal simultaneously with the Berlin blockade and with the communist’s victory in the Chinese Civil War. Fuchs was convicted in England in 1950. Closer to home, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were arrested in 1950, also for passing along atomic secrets to the Soviet Union during WWII. Events seemed spiraling out of control. Within months of the Soviet Union having successfully tested their first atomic bomb (years before U.S. intelligence had predicted), Mao Zedong’s communist army gained control of the Chinese mainland, forcing the U.S.-backed Chiang Kai-shek to flee to Formosa. Months later, communists in North Korea invaded South Korea. All of these events had a direct impact on McCarthyism.

But other forces also contributed to McCarthyism. Many had long been wary of liberal, progressive policies, particularly Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. As far as many were concerned, “New Dealism,” was heavily influenced by communism, and by the end of WWII it had ruled American society for a dozen years. During the McCarthyism era, much of the danger they saw was about vaguely defined “communist influence” rather than direct accusations of being Soviet spies. In fact, throughout the entire history of post-war McCarthyism, not a single government official was convicted of spying. But that didn’t really matter to many Republicans. During the Roosevelt Era they had been completely shut out of power. Not only did Democrats rule the White House, they had controlled both houses of congress since 1933. During the 1944 elections the Republican candidate Thomas Dewey had tried to link Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal with communism. Democrats fired back by associating Republicans with Fascism. By the 1946 midterm elections, however, fascism had largely been defeated in Europe, but communism loomed as an even larger threat. Republicans found a winning issue. By “Red-baiting” their Democratic opponents—labeling them as “soft on communism,” they gained traction with voters.

One of the early successful Red-baiters was an ex-Navy officer from California named Richard Nixon. Nixon was recruited into politics by a committee of Republicans in California’s 12th congressional district who were bent on ousting incumbent Democrat Jerry Voorhis, a loyal supporter of the New Deal with a liberal voting record. Nixon came on strong and suggested that Voorhis’s endorsement by a group linked to communists meant that Voorhis must have radical left-wing views. In reality, Voorhis was a staunch anti-communist. He had once been voted by the press corps as the “most honest congressman.” But Nixon was able to successfully link Voorhis to the group, even though Voorhis refused to accept any endorsement unless it first renounced communist influence. Nixon won by over 15,000 votes. Meanwhile, another young WWII veteran from Wisconsin named Joe McCarthy won election to the U.S. Senate.

In those mid-term elections of 1946, the Republican Party won a majority in both the House and Senate. Much of that had to do with voter discontent with Harry Truman over his refusal to lift wartime price controls and his handling of several high-profilelabor disputes, but Red-baiting played a role. Being in the majority meant control of committee chairs, including the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had existed in various forms since 1934. This committee, known as HUAC, initiated a major revival of anticommunist investigations.

Reacting in part to Republican gains in the midterm elections and allegations that he was soft on communism, President Truman initiated a loyalty review program for federal employees in March 1947. The background investigations were carried out by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). This was a major assignment that led to a dramatic increase in the number of agents in the Bureau. It also gave more power to the FBI’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, who reigned over the agency for decades as an untouchable. Possessed with an ego that required constant flattering by his subordinates, even Congressmen and Senators were reluctant to challenge his methods (which included illegal wiretapping) for fear that he might have files onthem. The legendary Hoover’s extreme anti-communism and loose standards of evidence resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Hoover insisted on keeping secret the identity of his informers, so most of the investigated were not allowed to cross-examine or even know who had accused them. In many cases they were not even told what they were accused of.

In October 1947 HUAC investigated whether communist agents and sympathizers had been secretly planting communist propaganda in American films. This was the moment for conservatives to push back against the leftist politics of the Hollywood elite going back to the 1930s. “Friendly” witnesses who testified before the committee included Walt Disney, Screen Actors Guild president (and future U.S. President) Ronald Reagan, and actor Gary Cooper. The friendly witnesses testified to the threat of communists in the film industry, and some of them named names of possible communists. HUAC assembled a witness list of forty-three people, some of whom were known to have been members of the American Communist Party. Nineteen of the forty-three said they would not give evidence, and of those, eleven were subpoenaed to appear before HUAC and answer questions. One of these ultimately cooperated. The remaining ten, known as the “Hollywood Ten,” were labeled “unfriendly” witnesses.

Other Hollywood elite also resisted HUAC. They founded the Committee for the First Amendment as a protest against government abuse. Members included Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Henry Fonda, Gene Kelly, Edward G. Robinson, Judy Garland, Katharine Hepburn, Groucho Marx, Lucille Ball, and Frank Sinatra. In October 1947 the group traveled to Washington to watch the hearings. After each unfriendly witness was sworn in, he was asked the same question: “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”

Membership in the Communist Party was not and had never been illegal. Each of the witnesses hadat one time or another been a member (most still were), while a few had been in the past and only briefly. The unfriendly witnesses refused to answer the questions on First Amendment principles. Sometimes the questioning generated intense hostility, as in the case of screenwriter John Howard Lawson’s testimony. After the hearings, proceedings against the Hollywood Ten took place in the full House of Representatives. On November 24, they voted 346 to 17 to cite the Hollywood Ten for contempt of Congress. The next day Motion Picture Association of America president Eric Johnston issued a press release declaring that the Hollywood Ten would be fired or suspended without pay until they were cleared of contempt charges and had sworn that they were not communists. This was, in effect the first Hollywood blacklist. The Hollywood Ten were convicted and sentenced to one-year prison terms.

Humphrey Bogart felt enough pressure from the backlash of his involvement with the Committee For The First Amendment that he felt compelled to publish an article in Photoplay titled, “I’m No Communist.”

The investigation of the entertainment industry continued for several years. In June 1950 a right-wing journal called Counterattack published a book with the names of 151 actors, writers, directors, producers, musicians, broadcast journalists, and other entertainers, and the organizations they were linked to which were supposedly communist. No evidence was provided linking these organizations to communism. Many were labor organizations and newsletters. Called Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, it claimed these entertainers were actively engaged in manipulating the entertainment industry. Red Channels effectively blacklisted these entertainers. Executives in the movie and growing television

industries avoided hiring persons on the list to avoid controversy and risk losing advertising sponsors. For example, veteran film and radio actress Jean Muir was scheduled to play the character of Mrs. Aldrich in the new NBC television series, The Aldrich Family. Just weeks before the season premiere, Muir was listed in Red Channels. After receiving a flood of phone calls, the show’s sponsor, General Foods, canceled the first episode, fired Muir, and replaced her with another actress. The first episode was quickly reshot and aired a week later. Lawrence Johnson, an official in the National Association of Supermarkets, pressured the manufacturers of products sold in supermarkets to not buy TV advertising for any program that used an actor listed in Red Channels.

When the TV series Danger tried to use one of these actors, Johnson told the show’s sponsor, the makers of Amni-dent toothpaste, that all grocery stores would put up a sign next to Amni-dent suggesting their programs employed communists. Meanwhile, they would put a sign next to a competitor’s toothpaste, Chlorodent, saying, “Its programs use only pro-American artists and shun Stalin’s little creatures.” The actor in question was quickly removed. By 1951, the major radio and TV networks had set up their own blacklist offices to clear actors with people like Johnson, always over the phone. The voice at one end would go down the list of proposed actors, and the person on the other end would respond with “yes” or “no.” Questions were not asked. Many careers were ruined, and nervous movie studios stayed away from scripts with plots that could be seen as controversial, resulting in nearly a decade of fluff, westerns, and patriotic war films.

After his election, Richard Nixon quickly joined HUAC, where he played a crucial role in the investigation of a long-time government worker named Alger Hiss, whose distinguished career chiefly involved liberal causes. Hiss had been part of the US delegation at Yalta where, according to some, the country had been sold out to the Soviets by Roosevelt. On August 3, 1948, a senior editor at Time magazine and former communist named Whittaker Chambers testified before HUAC that Hiss had secretly been a communist while in federal service in the late 1930s. To clear his name, Hiss requested and was granted an audience before HUAC, where he denied the charges and impressed them with his dignity and presence. The committee seemed satisfied, but Richard Nixon pressed them to investigate further.

After being asked to identify Chambers from a photograph, Hiss indicated that his face “might look familiar” and requested to see him in person. When he later confronted Chambers in a hotel room, with HUAC representatives present, Hiss claimed that he had known Chambers as “George Crosley”, a freelance writer. Hiss said he had sublet his apartment to Crosley in the mid-1930s and had given him an old car. After Chambers publicly restated his claim that Hiss was a communist, Hiss sued Chambers for libel.

To bolster his claim that Hiss was a communist, Chambers produced sixty-five pages of retyped State Department documents and four pages in Hiss’s own handwriting of copied State Department cables which he claimed to have obtained from Hiss in the 1930s; the typed papers having been retyped from originals on the Hiss family’s Woodstock typewriter. Both Chambers and Hiss had previously denied committing espionage. By introducing these documents, Chambers admitted that he had lied to the committee. Chambers then produced five rolls of 35 mm film, two of which contained State Department documents. Chambers had hidden the film in a hollowed-out pumpkin on his Maryland farm, and they became known as the “pumpkin papers”.

Too much time had passed to charge Hiss with espionage, so he was charged instead with perjury—lying under oath. Chambers admitted to the same offense, but as a cooperating government witness he was never charged. The trial ended in a hung jury, and Hiss was retried. At both trials, key testimony was given by expert witnesses who matched the typed documents with the old Hiss family typewriter. Hiss was found guilty on both counts of perjury and received two concurrent five-year sentences, of which he eventually served 44 months.

The Hiss conviction was a boost for Richard Nixon’s career and for the Republican Party. In 1948, after only 2 years in power, they had lost their majorities in the House and Senate to the Democrats.

And in a real shocker, President Truman had narrowly defeated Republican candidate Thomas Dewey. With the 1950 midterm elections just half a year away, Republicans pressed their political advantage by attacking Democrats. Congressman Karl E. Mundt of South Dakota demanded that Truman should now help to “ferret out [those government employees] whose Soviet leanings had ruined America’s foreign policy.” Congressman Harold E. Velde of Illinois charged that Russian espionage agents were running loose all over the country, and Congressman Robert F. Rich of Pennsylvania suggested that Secretary of State Dean Acheson was working for Stalin. The Republicans adopted a platform in which they deplored “the dangerous degree to which communists and their fellow travelers have been employed in important Government posts,” and they denounced the “soft attitude of this Administration toward Government employees and officials who hold or support communist attitudes. At Lincoln Day dinners around the nation, Republicans were telling receptive audiences about the internal threat proven by the Hiss conviction. Congressman William S. Hill of Colorado said, “we found them heavily infiltrated into high policy-making positions…we were fully vindicated.” Richard Nixon declared that the Hiss case was only “a small part of the whole shocking story of communist espionage in the United States.” It was in this atmosphere of renewed attacks against Democrats that Senator Joe McCarthy emerged.

On February 9, 1950, at the Republican Women’s Club of Wheeling, West Virginia, Senator Joe McCarthy gave his Lincoln Day speech. Much of it was cut and pasted from speeches and testimony delivered in Washington and already public record. But then McCarthy produced something new. His exact words will never be known, but according to radio and newspaper men who followed his rough draft as he spoke, McCarthy took out a piece of paper, waved it around, and shouted, “I have here in my hand a list of 205–a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.” Communists in the State Department represented a potential threat to national security. But McCarthy had no such list. His source was a four-year-old letter, already published in the Congressional Record, from then Secretary of State James Byrnes to a U.S. Congressman. In the letter, Byrnes explained that a screening of 3,000 federal employees transferred into the State Department from wartime agencies had resulted in recommendations against the permanent employment of 285. Of these 285, the employment of 79 had already been terminated. By subtracting 79 from 285, Senator McCarthy had his so-called 205 State Department communists.

The speech was red meat to the audience to which it was delivered. McCarthy did not anticipate, and was taken aback by the massive media response to it. From Wheeling, McCarthy flew to Salt Lake City. While changing planes in Denver, he was surrounded by reporters eager to see the list of communists. McCarthy agreed to show them the list, and then claimed to have left it in his baggage on the plane. Reporters also presented to him a State Department denial of his charges. McCarthy scoffed at the statement and told reporters he had “a complete list of 207 ‘bad risks’ still working in the State Department.”

By the time he reached Salt Lake City, he had recovered enough from his surprise to more effectively engage the press. Now he claimed that there were two lists. The 205 were the “bad risks” he had mentioned in Denver, still working in the State Department. There were, he now claimed, fifty-seven “card-carrying communists” in the State Department. McCarthy told reporters that he would gladly furnish the names if the department would open their loyalty files. When McCarthy reached Reno, Nevada, he was given a telegram from Deputy Undersecretary of State John E. Peurifoy, demanding McCarthy’s information. Instead of complying, McCarthy telegraphed President Truman. He told the President that, despite the “blackout” on loyalty files, he had been able to assemble the names of fifty-seven communists in the State Department. McCarthy demanded that Truman open their files. “Failure on your part will label the Democratic Party of being the bedfellow of international communism,” he wrote. Peurifoy publicly denied the McCarthy accusations one by one. Senator McCarthy, meanwhile, went on to Huron, North Dakota. It would be another week before he returned to Washington.

Senator McCarthy returned to the Senate on February 20 with his briefcase bulging with photocopies of some 100 files prepared in 1947 from the State Department loyalty files by team of investigators from the House Appropriations Committee, now referred to as the “Lee list”. The Lee List was outdated, biased, and inaccurate, but in a lengthy Senate speech, McCarthy claimed that he had pierced the “iron curtain” of State Department secrecy and with the aid of “some good, loyal Americans in the State Department,” had compiled an alarming picture of espionage and treason. He now revised his number to 81, and proceeded to present a somewhat case-by-case analysis of these 81 “loyalty risks” employed at the State Department.

By comparing McCarthy’s speech with the Lee List, it’s clear that the Senator was engaged in a full-fledged campaign of distortion and lies. He omitted key findings that had exonerated the person in question, and added his own made-up facts, that a subject “had top secret clearance”, or was “a very close associate of active Soviet agents.” Sometimes the exaggeration was subtle, but yet incredibly important. A “subject” on the Lee list became “an important subject.” Three people “with Russian names” became “three Russians.” Words like “reportedly” and “allegedly” disappeared, and “may be” and “may have been” were replaced with “is” and “was.” Of one person the Lee document said was “inclined toward communism,” McCarthy simply declared “he was a communist.” A “liberal” became “communistically inclined.” The following comparison shows the shocking extent to which Senator McCarthy distorted information:

From Lee case no. 40:

The employee is with the Office of Information and Educational Exchange in New York City. His application is very sketchy. There has been no investigation. (C-8) is a reference. Though he is 43 years of age, his file reflects no history prior to June 1941.

McCarthy’s interpretation:

This individual is 43 years of age. He is with the Office of Information and Education. According to the file, he is a known communist. I might say that when I refer to someone as being a known communist, I am not evaluating the information myself. I am merely giving what is in the file. This individual also found his way into the Voice of America broadcast. Apparently the easiest way to get in is to be a communist.

McCarthy’s speech was a lie, but Republicans went along for political gain. Democrats tried to pin him down on his list, and McCarthy first agreed, and then refused to name names. He couldn’t have named any names if he had wanted to. The Lee List used only case numbers. He did not get a copy of the key to the list, matching names with the case numbers, until several weeks later. Democrats had little choice but to agree to the creation of a committee to investigate McCarthy’s charges. They also acceded to Republican demands that the Congress be given the authority to subpoena the loyalty records of all government employees against whom charges would be heard. Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon insisted that the hearings be conducted in public, but even so, the investigators were able to take preliminary evidence and testimony in executive session (in private). The final Senate resolution authorized “a full and complete study and investigation as to whether persons who are disloyal to the United States are, or have been employed by the Department of the State.”

Joe McCarthy was a shrewd politician, but he was also insecure. Having grown up in a poor, Irish-Catholic family, he was extremely resentful of his class status. He especially hated liberal elites, men like Alger Hiss and Dean Acheson, whom he saw as snobs, and he did not handle perceived criticism well. McCarthy hid his insecurities in alcohol, and he relished the attention paid to him by reporters, whom he would court with frequent after-hours drinking binges. He loved to please them and especially loved just being one of the boys. His hard-drinking tendencies soon blossomed into full-blown alcoholism. He drank a huge amount of alcohol in short periods. As his drinking progressed he took to eating a quarter-pound stick of butter when he drank, which he claimed helped him hold his liquor. The Washington Press Corps by and large went along with McCarthy’s allegations. The access he gave them during his time in the spotlight was extremely unusual, and they were reluctant to dig very deep into his stories because to do so might threaten what was for them a dream news story. McCarthy’s only plan was to continue to make headlines, and to do that he would have to continually make new accusations. He was able to do that for four long years.

The Tydings Committee hearings, chaired by Democratic Senator Millard Tydings, began on March 8, 1950. Democrats hoped to use the hearings to discredit McCarthy. Tydings himself was reported to have said, “Let me have him for three days in public hearings, and he’ll never show his face in the Senate again.” During the hearings, McCarthy moved on from his original unnamed Lee List cases and used the hearings to make charges against nine specific people. Some never had or no longer worked for the State Department. McCarthy claimed that one man was a “top Russian spy,” but he produced no substantial evidence to support his accusations

The term “McCarthyism” was coined a few weeks into the hearings by Washington Post cartoonist Herbert Block (Herblock). His March 29, 1950 cartoon titled “You Mean I’m Supposed to Stand on That?” depicted an elephant (symbol of the Republican Party) being pushed and shoved toward a platform made up of buckets of tar (a reference to the arcane punishment of “tarring and feathering”). The barrel directly beneath the platform is labeled, “McCarthyism.” Republicans are often criticized by historians for allowing McCarthy to do their dirty work while they took the high road and the political gain. But a few Republicans did stand up, for a moment at least.

During the Tydings hearings, Senator Margaret Chase Smith became the first Republican to openly criticize McCarthy. She and six other Republicans issued a “Declaration of Conscience.” President Truman led the Democrats against McCarthy. At a news conference he said that McCarthy was trying to “sabotage the foreign policy of the United States.” Such behavior, he said, “is just as bad in this cold war as it would be to shoot our soldiers in the back in a hot war.”

On July 14 the Tydings Committee issued its report. Written by the Democratic majority, it concluded that the individuals on McCarthy’s list were neither communist nor pro-communist, and that the State Department had an effective security program.

McCarthy’s charges, it went on, were a “fraud and a hoax” that had confused and damaged the American people. Republicans responded that Tydings was guilty of “the most brazen whitewash of treasonable conspiracy in our history.” The full Senate voted three times on whether to accept the report, and each time the voting was precisely divided along party lines.

But that fall, with the midterm elections looming, the Democratic-controlled Congress passed The McCarran Internal Security Act, which tightened immigration and deportation laws and allowed for the detention of dangerous, disloyal, or subversive persons in times of war or “internal security emergency”. Truman called the bill “the greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798,” and vetoed it, but his own party joined with Republicans to override his veto.

In the 1950 midterm elections, Senator McCarthy campaigned for John Marshall Butler in his race to unseat Senator Millard Tydings, who had chaired the Tydings Committee. McCarthy accused Tydings of “protecting communists” and “shielding traitors.” McCarthy’s staff helped produce a campaign publication containing a photograph doctored to make it appear that Tydings was in intimate conversation with the General Secretary of the Communist Part of the United States. Butler won by a landslide. A Senate subcommittee later investigated this election and referred to it as “a despicable, back-street type of campaign,” but the damage had been done. Republicans won in all of the races where McCarthyism came into play. Democrats dropped 28 seats in the House and 5 in the senate (including one to Richard Nixon), but still maintained their majority in both houses. McCarthy was credited with much of the midterm results, and thus became one of the most powerful men in the Senate. The days when he would be openly challenged by members of his own party were over.

McCarthyism got a boost when the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, accused of spying for the Soviet Union, began on March 6, 1951. The main prosecution witness was Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass, who claimed to have passed along atomic bomb-related drawings to Julius, along with notes typed up by Ethel (Greenglass later recanted his testimony and claimed that he did it to protect himself and his family, not realizing the death penalty would be invoked). The Rosenbergs were convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 and sentenced to death. Despite a grassroots campaign to have the conviction overturned, on June 19, 1953, the husband and wife were executed by electric chair. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, former Soviet agents came forward to claim the Rosenbergs were not involved in espionage for the Soviet Union. Other evidence has since surfaced, however, and the general consensus now is that Julius Rosenberg did pass on sensitive atomic information to the Soviet Union—information they already had. The debate continues about Ethel’s involvement, with most historians arguing that she was either not involved or knew about her husband’s activities but did not participate.

Having cut deeply into Democratic Party majorities, Republicans set their sights on the 1952 elections, and McCarthyism played a key role. On June 14, 1951, in a Senate speech, Joe McCarthy launched a savage attack against George C. Marshall, the highly respected statesman and general best remembered as President Roosevelt’s Army Chief of Staff during WWII and as the architect of the Marshall Plan for post-war reconstruction of Europe (for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953). McCarthy began by recapping recent Chinese history. He then charged that Marshall was directly responsible for “the loss of China,” and for the loss of America’s world power and stature. He directly accused Marshall of “a conspiracy so immense as to dwarf any venture in the history of man; a conspiracy so black that, when it is finally exposed, its principals shall be forever deserving of the maledictions of all honest men.” Democrats were outraged. In a full-page editorial, Collier’s magazine called the speech “a new high for irresponsibility,” and called on Republican leaders to disassociate themselves from McCarthy’s “senseless and vicious charge.” The press, however, hailed the speech. Soon McCarthy was again claiming that the State Department was harboring communists.

For the Presidency, Republicans took the moderate road and nominated General Dwight D. Eisenhower, former Supreme Allied Commander during WWII. To balance the ticket and give it some anti-communist credentials, Senator Richard Nixon was tapped to be Vice President. Eisenhower’s opponent was Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, who had been nominated after President Truman, sensing defeat, had declined to run again. Eisenhower had been shocked and outraged by McCarthy’s attack on Marshall, who had been one of Ike’s most important mentors in the military. But when Eisenhower campaigned in Wisconsin, he toured with McCarthy. In draft versions of a speech Eisenhower delivered in Green Bay, he had included a strong defense of Marshall, which was a direct rebuke of McCarthy’s attacks. However, Eisenhower buckled under pressure from his campaign staff to delete it. Instead, Eisenhower declared that while he agreed with McCarthy’s goals, he disagreed with his methods. The deletion was discovered by a reporter for The New York Times and featured on their front page the next day. Eisenhower was widely criticized for giving up his personal convictions, and the incident became the low point of his campaign.

But Eisenhower was popular with Americans. His staff was quick to recognize that television had ushered in a new era of campaigning. The nuanced, intellectual political speeches of old did not play nearly so well on television as did the “sound bite,” a compression of a candidate’s appeal (or the opponent’s weaknesses) into a simple slogan and a one minute television spot. “Eisenhower, man of peace” was one. “I like Ike” (Eisenhower’s nickname) was another. It worked. Dwight Eisenhower became the first Republican president in 20 years. The Republican Party also held retook majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. After being elected president, Eisenhower made it clear to those close to him that he did not approve of McCarthy (who was reelected that year), but he never directly confronted McCarthy or criticized him by name in any speech. And Eisenhower strengthened and extended Truman’s loyalty review program, while decreasing the avenues of appeal available to dismissed employees.

With Republicans now firmly in power, McCarthyism branched out into other areas of American society, including education. Some attacked progressive education reforms with publications like “How Red is the Little Red Schoolhouse?” and, “Progressive Education Increases Delinquency.” Pressure from grass roots organizations had a chilling effect on free speech and resulted in the removal of such books as Robin Hood from school libraries because they taught communist values (Robin Hood did, after all, redistribute the wealth by robbing the rich and giving to the poor). The Board of Regents in the state of New York established a special commission to investigate textbooks for patriotism. Teachers with liberal views or who supported the teacher’s union had their loyalty questioned.

In 1953 Senator McCarthy was made chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, which included the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. The mandate of this subcommittee was flexible enough to allow McCarthy to use it for his own investigations of communists in the government. McCarthy first examined allegations of communist influence in the Voice of America, the government institution responsible for broadcasting an American point-of-view over the radio and television stations overseas. He then turned to the overseas library program of the State Department. Card catalogs of these libraries were searched for works by authors McCarthy deemed inappropriate. McCarthy then recited the list of supposedly pro-communist authors before his subcommittee and the press. Yielding to the pressure, the State Department ordered its overseas librarians to remove from their shelves “material by any controversial persons, communists, etc.” Some libraries actually burned the newly forbidden books.

One of the most prominent attacks on McCarthy’s methods was an episode of the television documentary series See It Now, hosted by journalist Edward R. Murrow, which was broadcast on March 9, 1954. Titled “A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy”, the episode consisted largely of clips of McCarthy speaking. In these clips, McCarthy accuses the Democratic party of “twenty years of treason”, describes the American Civil Liberties Union as “listed as ‘a front for, and doing the work of’, the Communist Party”, and berates and harangues various witnesses, including General Zwicker.

In his conclusion, Murrow said of McCarthy:

His primary achievement has been in confusing the public mind, as between the internal and the external threats of Communism. We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason…We proclaim ourselves, as indeed we are, the defenders of freedom, wherever it continues to exist in the world, but we cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home. The actions of the junior Senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it—and rather successfully.

At the end of the March 9 broadcast, Murrow offered McCarthy a chance to rebut the story. McCarthy called Murrow a liar and accepted the offer, but said he needed time to prepare. In the meantime, See It Now ran another episode critical of McCarthy on March 16, this one focusing on the case of Annie Lee Moss, an African-American army clerk who was falsely accused by McCarthy of having communist connections. McCarthy’s reply was broadcast on See It Now on April 6. Instead of addressing Murrow’s reporting, he made a number of charges against the reporter, including that he had helped with Soviet espionage and propaganda efforts. As usual, he had no evidence. Murrow refuted the charges, but McCarthy’s accusations did not go over well with See It Now viewers.

In the spring of 1954, McCarthy’s committee began an investigation into the United States Army. Earlier, McCarthy had made headlines with stories of a dangerous spy ring among Army researchers, but ultimately nothing came of this investigation. McCarthy next turned his attention to the case of a U.S. Army dentist who had been promoted to the rank of major despite having refused to answer questions on an Army loyalty review form. McCarthy’s handling of this investigation, including a series of insults directed at a brigadier general, led to the Army-McCarthy Hearings, with the Army and McCarthy trading charges and counter-charges for 36 days before a nationwide television audience. The official outcome of the hearings was inconclusive, but they had a hugely negative effect on McCarthy’s popularity. In one case, McCarthy was caught having heavily edited a photograph entered into evidence, and in another case, he was caught having fabricated a letter and presenting it as evidence from the FBI. Many in the audience saw him as a bully, reckless and dishonest. Television had exposed McCarthy in a way that newspapers never could.

During these hearings other popular culture began to push back against McCarthyism. On May 30, 1954, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation aired Reuben Ship’s “The Investigator,” a satire of HUAC and McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. The left gave it positive reviews, but the right excoriated the production as anti-American propaganda. Just days later, Four Star Records released Cactus Pryor’s “Point of Order, with the Senator and the Private,” which mocks the committee for its focus on triviality, and the absurdity of McCarthy’s suspicious nature (he objects to quoting Shakespeare until he’s cleared as not being a Communist).

Late in the hearings, Senator Stuart Symington made an angry and prophetic remark to McCarthy: “The American people have had a look at you for six weeks,” he said. “You are not fooling anyone.”In Gallup polls of January 1954, 50% of those polled had a positive opinion of McCarthy. In June, that number had fallen to 34%. In the same polls, those with a negative opinion of McCarthy increased from 29% to 45%.

The most famous incident in the hearings was an exchange between McCarthy and the army’s chief legal representative, Joseph Nye Welch. On June 9, the 30th day of the hearings, Welch challenged Roy Cohn to provide U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr. with McCarthy’s list of 130 Communists or subversives in defense plants “before the sun goes down”. McCarthy stepped in and said that if Welch was so concerned about persons aiding the Communist Party, he should check on a man in his Boston law office named Fred Fisher, who had once belonged to the National Lawyers Guild, which Brownell had called “the legal mouthpiece of the Communist Party”. In an impassioned defense of Fisher, Welch responded, “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never gauged your cruelty or your recklessness.” When McCarthy resumed his attack, Welch interrupted him: “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” When McCarthy once again persisted, Welch cut him off and demanded the chairman “call the next witness”. At that point, the gallery erupted in applause and a recess was called. In less than a year, McCarthy was censured by the Senate and his position as a prominent force in anti-communism was essentially ended. Despite the years of controversy over McCarthy, President Eisenhower never did take a public stand against him. Some historians argue that, had he done so, the Senator’s influence might have ended much sooner.

Months later, in the midterm elections, Democrats swept into control of the House and Senate. McCarthy had become a liability to his party. In less than a year, McCarthy was censured (reprimanded) by the Senate and his position as a prominent force of anti-communism ended. McCarthy finished his term, but he was now universally shunned by his own party. And when the headlines ended, so did the attention paid to him by the media, which McCarthy had relished above all else. He declined rapidly, both physically and emotionally. He sometimes appeared in the Senate incoherently drunk. He died on May 2, 1957, at the age of 48, from liver illness brought on by his heavy drinking.

Although McCarthy himself was gone, the death of McCarthyism took much longer. General hysteria about communism continued in many forms by various super patriots. In the summer of 1954, a branch of the American Legion in Illinois denounced the Girl Scouts, calling the “one world” ideas printed in their publications “un-American.” When playwright Arthur Miller applied for a renewal of his passport in 1956, HUAC took the opportunity to call him in to testify. Years earlier, in 1952, Miller had written The Crucible, in which he compared the Salem Witch Trials to McCarthyism. Miller gave a detailed account of his political activities, but refused to name names (the chairman of the committee had assured him that he would not be asked to do so. He lied). As a result, a judge found Miller guilty of contempt of Congress in May 1957. Miller was sentenced to a $500 fine or thirty days in prison, blacklisted, and disallowed a US passport.

With McCarthy out of the picture, the roll of attack dog fell squarely on the shoulders of Vice President Nixon. During the 1954 midterm elections, Nixon campaigned relentlessly for Republican candidates. He traveled 26,000 miles through ninety-five cities in thirty-one states. At each stop he attacked Democrats as the party of Korea, communism, and corruption. Eisenhower, meanwhile, again took the high road. Despite Nixon’s repeated smears of Democrats, Republicans lost control of both houses of Congress that November. Both parties, however, continued to make internal security a high priority. HUAC Investigations continued throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s.

May 27, 1954: Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic bomb, then working as a consultant to the Atomic Energy Commission, was stripped of his security clearance after a four-week hearing. Oppenheimer had received a top-secret clearance in 1947, but was denied clearance in the harsher climate of 1954.

June 14, 1954: In a gesture against the “godless communism” of the Soviet Union, the phrase “under God” was incorporated into the Pledge of Allegiance by a Joint Resolution of Congress amending §7 of the Flag Code enacted in 1942.

August 24, 1954: The Communist Control Act was signed by President Eisenhower. It outlawed the Communist Party of the United States and criminalized membership in, or support for, the Party.

July 30, 1956: In another gesture against the “godless communism” of the Soviet Union, President Eisenhower signed a law adding “In God we trust” to paper currency and making it the official motto of the United States.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Cold War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Cold War .

This article is also part of our larger selection of posts about American History. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to American History.